Work camps have been operating for male prisoners in Western Australia since 1998. The primary goals of work camps are to provide prisoners with the opportunity to get involved in meaningful work in a community environment, repay a debt to society, develop vocational and personal skills and, for those prisoners nearing the end of their sentence, increase the chances of a successful transition from prison to the community.While Aboriginal men are underrepresented in terms of minimum security assessments, they are overrepresented in terms of work camp placement when system-wide figures are considered. As of June 2012, Aboriginal men comprised 27 per cent of the minimum security population but 51 per cent of the work camp population.

However, these figures are primarily the result of the location and size of the work camps at Warburton, Wyndham and Millstream, which are predominately populated by Aboriginal prisoners. In the same way that these work camps are predominately comprised of Aboriginal prisoners, the work camps at Walpole and in the Wheatbelt have been predominately populated by non-Aboriginal prisoners. As a result, Noongar men from the South West have enjoyed very little of the benefits of a work camp.

Significant changes have occurred in the location of work camps since 2009. Both the Bungarun work camp in Derby and the Mt Morgan’s work camp near Laverton have closed and the work camp for Wooroloo Prison Farm shifted from Kellerberrin to Wyalkatchem, before moving again to Dowerin. In addition, Pardelup transitioned from being a work camp to a prison farm. However, both the capacity and number of work camps has remained relatively consistent over the period examined.

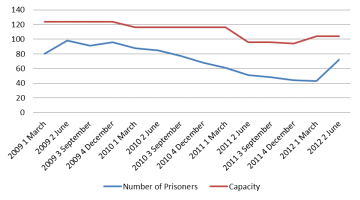

Despite the relative consistency in capacity, the number of prisoners actually accessing work camps has fluctuated considerably. Through late 2011/early 2012, work camps were operating well under capacity (see Figure 3), with numbers substantially lower than at the start of the time period. By June 2012, however, there had been a revitalisation in work camp numbers and numbers were at their highest level since 2010, although still at only 69 per cent capacity.

Figure: Prisoners in Work Camps versus Total Work Camp Capacity 2009 – 2012

While work camps were, overall, operating at well below capacity at the end of June 2012 most individual work camps were at or near capacity. The population of Warburton work camp had more than tripled in the three months ending June 2012, and numbers at Wyndham work camp more than doubled. The new work camp at Dowerin also increased its numbers quickly since opening in February 2012, and 17 prisoners were stationed there by the end of June 2012.

Despite these individual improvements, overall work camps were still only operating at 69 per cent capacity. This has occurred despite there being a number of prisoners in potential feeder prisons who had been deemed suitable for supervised or unsupervised work camp placement. Table 3 shows the number of prisoners in the main potential feeder prisons who have been assessed for work camp suitability and were not in a work camp. In total, around 80 prisoners had been assessed as suitable but remained in a minimum security prison rather than a work camp.

It must be emphasised that placement at a work camp is voluntary and not all ‘suitable’ prisoners will want to go to a work camp because of family, cultural and other reasons. For example, men from Kalgoorlie may not be willing or ‘culturally qualified’ to go to the Warburton work camp. The findings of this audit and an examination of current eligibility criteria indicate that three key strategies need to be pursued in order to maximise the numbers of prisoners at work camps and to repay public investment:

- Increase the pool of eligible prisoners by examining ways to increase the number of Aboriginal people attaining minimum security classification and, from there, clearance for a work camp placement.

- Increase the pool of eligible prisoners by reassessing some of the current exclusions. For example, the 24 Indonesian prisoners at Pardelup are essentially deemed unsuitable solely because they are subject to deportation. There are also a large number of prisoners at the Bunbury Pre-Release Unit, Greenough Unit Six, and Karnet Prison Farm, who appear to be automatically considered as ‘not suitable’. In many cases this may be because of the nature of their offence but the high figures do suggest there may be some room for re-consideration.

- Increase the number of those prisoners assessed as work camp suitable who are actually placed at the work camps.