The key issues across Western Australia’s custodial estate

Each year the Office’s Annual Report highlights key issues and challenges impacting the custodial estate in Western Australia. The following issues were raised in the 2022-2023 Annual Report.

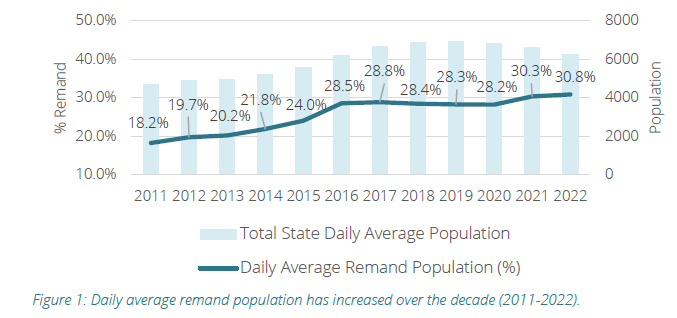

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of people entering custody on remand, bringing into question the treatment of unsentenced people. In Western Australia, the daily average unsentenced population across the adult custodial estate has progressively increased over the past decade. In 2011, 18 per cent of the daily average population were unsentenced. This increased to nearly 31 per cent by 2022, despite a decrease in the total population.

This increase in the unsentenced population has impacted some facilities more than others. Casuarina Prison – a maximum-security facility intended for sentenced prisoners – has seen a 358 per cent increase in the number of unsentenced prisoners placed there. It now holds a vast number of unsentenced prisoners including many who cannot be placed at Hakea Prison for security reasons.

This is despite Hakea being the primary remand centre for adult males. As a result, Hakea has taken onboard a large proportion of sentenced prisoners, despite not being equipped to meet their needs (OICS, 2022C).

Large increases in the unsentenced population have also occurred at many regional facilities, including Broome Regional Prison (256%), Greenough Regional Prison (189%), Albany Regional Prison (99%) and Bunbury Regional Prison (99%).

The demographic of unsentenced prisoners is also changing. For instance, Aboriginal remandees now exceed non-Aboriginal remandees. In 2011, 49 per cent of remandees received into prison identified as Aboriginal. Following a decline between 2013 and 2016, the proportion of Aboriginal remandees hovered around 46 – 47 per cent, before surging to 51.3 per cent in 2022. The reason for this surge is unclear.

Over the decade there has also been an increase in females being received on remand. In 2011, nearly 13 per cent of all prisoners received on remand were women. This increased to 15 per cent in 2022, following an earlier peak of 17 per cent in 2018.

And, prisoners being received into custody are on average older than they were a decade ago. The average age of prisoners received on remand has increased from 30.8 years in 2011 to 34.2 in 2022. This aligns with our review into older prisoners, which found the custodial population in Western Australia was ageing (OICS, 2021A). This shift in the number of unsentenced people in custody brings into consideration the treatment and rights of those remanded in custody.

The Guiding Principles for Corrections in Australia notes that remand prisoners should be subjected to fewer restrictions than sentenced prisoners (CSAC, 2018).

The Mandela Rules also notes that unconvicted prisoners should be kept separate from convicted prisoners, should have single-bed accommodation, be able to wear their own clothes, and have the option to procure their own food at their own expense (UNODC, 2015).

However, in practice, there is often very little difference between the conditions for remand and sentenced prisoners. Remand prisoners held in any Western Australian prison do not wear their own clothes, do not have a right to their own single-bed accommodation, and are not procuring their own food. And, at many prisons across Western Australia sentenced and unsentenced prisoners live, work and recreate together.

Until recently, the Prison Regulations 1982 also allowed for people remanded in custody to receive daily visits from friends and family, as was practicable. In reality this was very difficult for prisons to facilitate and rarely occurred. Amendments were passed in 2022 limiting visits to twice per week and subject to the capacity of the prison’s visiting facilities. The rights of remandees to visits is now only marginally different to sentenced prisoners, who continue to be entitled to at least one social visit per week.

There is no doubt that the increase in people remanded in custody has created challenges in the custodial estate. Still, remandees are unconvicted and have a presumption of innocence until their trial. The treatment and conditions of these people should reflect this important difference. The reality for many is that their time on remand is not spent undertaking productive activity.

Rehabilitation of offending behaviours and the development of pro-social skills is a key objective of incarceration. Through rehabilitation, people in custody reduce their risk of re-offending. Ineffective, inappropriate or inaccessible rehabilitation efforts can undermine this objective.

One of the most important rehabilitation interventions is the completion of criminogenic treatment programs that prisoners are assessed as needing. As of May 2023, there were 1,835 prisoners who collectively had been assessed as requiring 3,440 offending-related treatment programs. Yet only 35 per cent of these programs had been completed. As part of our monitoring, we regularly assess the suite of rehabilitation programs available across the custodial estate and the barriers prisoners may face accessing these.

One such barrier is that since 2018 delayed treatment assessments and the completion of initial individual management plans (IMPs) has continued to prevent many prisoners from accessing treatment programs. To reduce the backlog of assessments, the Department implemented the IMP Review Project between July 2019 and June 2022. Despite the project achieving process efficiencies, the backlog began to climb again after some initial positive progress. By June 2022, there were 738 prisoners awaiting an initial IMP. This has since grown to 811 as of 1 June 2023.

This backlog prevents these prisoners from having an opportunity to gain access to the rehabilitation they require to address their offending behaviour and successfully reintegrate back in their community.

But the difficulty does not stop once a prisoner has an IMP. Gaining access to required treatment programs has also proven difficult for many even after they have been assessed as needing them. For a program to run there needs to be enough prisoners with the same treatment need, in the same location, at the same time. This proves challenging for prisoners in regional facilities (particularly women) and specialist cohorts such as protection prisoners. As a result, many are required to transfer to a different facility to access their treatment program. Often this means moving away from family and friends or cultural connections. We continue to recommend the use of alternative delivery formats such as modularised, self-paced or remote learning that would improve accessibility and limit the need for prisoners to transfer (OICS, 2022F; OICS, 2022G; OICS, 2022H).

There are also concerns about the effectiveness of criminogenic programs on offer. During our inspection of Acacia Prison, concerns were raised that programs being delivered were out of date, in need of adaptation, and not responsive to people with learning difficulties or people from certain cultural backgrounds (OICS, 2023A). This issue was also raised at Roebourne Regional Prison. The Pathways addictions program – designed and developed for use in an urban American setting – was requiring significant adaptation to be relevant to the largely Aboriginal, regional-based cohort (OICS, 2022F). The lack of cultural relevance may partly explain a key finding of a Department-initiated review of programs that found Aboriginal men were likely to re-offend and return to custody regardless of program completion (Tyler, 2019).

Notwithstanding these issues, we have observed some positive developments in the offering of voluntary non-criminogenic programs. Acacia Prison hosted or provided access to a range of voluntary programs on substance use, family violence, gambling and victim awareness (OICS, 2023A).

Other programs helped develop skills to assist people transition to community life effectively, such as career development, parenting skills and financial planning. At Roebourne, the Yaandina Community Services was providing one-on-one counselling and Mission Australia was offering mental health and alcohol and other drugs (AOD) workshops (OICS, 2022F).

Our review into the supports available to perpetrators and survivors of FDV found there were multiple barriers to accessing treatment programs and limited voluntary programs with a focus on FDV (OICS, 2022H). More recently, however, the Department announced it was trialling a new family and domestic violence (FDV) program for victim-survivors at Bandyup Women’s Prison and Greenough Regional Prison. With community awareness of FDV issues increasing, this trial program is timely and will provide much needed support to women in custody nearing release.

Voluntary programs are an important piece of the rehabilitation puzzle. They are often more accessible to prisoners and do not require prior completion of treatment assessments. They also demonstrate a commitment to self-development and learning, which can be looked upon favourably by the Prisoners Review Board particularly where criminogenic treatment programs could not be accessed.

However, this does not diminish the need for an effective, accessible and deliverable suite of criminogenic treatment programs. It bears repeating that a key objective of incarceration is to provide a rehabilitative service to prevent people from re-offending. Recidivism comes with a financial cost – with adult prisoners costing on average $135,000 per year. But there is also a social cost we must consider – with offending impacting family, victims and the broader community.

Over the past year there has been considerable attention placed on the impact of staffing shortages on the operations of Banksia Hill Detention Centre. Our inspection of the facility in February 2023 was significantly hampered as a result of these shortages (OICS, 2023B).

But this issue is not isolated to Banksia Hill. Our recent reports for Acacia Prison (OICS, 2023A), Roebourne Regional Prison (OICS, 2022F) and Pardelup Prison Farm (OICS, 2022E) each highlighted how staffing shortages impacted daily operations. These impacts are also being observed in our current round of inspections, which are yet to be reported.

For some facilities, staffing issues stem predominantly from absences rather than vacancies. But at others it is due to vacancies that, for various reasons, cannot be filled. At Roebourne, we found the prison was being severely impacted by staffing shortages. Documents provided to us showed this was driven by the ongoing management of planned leave, secondments and workers’ compensation claims rather than actual vacancies.

Similarly, at the time we inspected Pardelup, a regional prison farm with a small number of uniformed staff, the facility had three suspended officers. As those positions were not vacant, they could not be backfilled. Four of the eight senior officer positions were also unavailable for various reasons. Pardelup sought assistance from Albany Regional Prison, who allowed their officers to do overtime shifts at the farm.

In other cases, staffing vacancies and high attrition rates were exacerbating the impact of staffing absences. This was particularly prevalent at Banksia Hill. At the time of inspection in February, there had already been 16 resignations for the year.

The Department has increased investment in the recruitment of new custodial staff to tackle vacancies, but a challenging employment market and ongoing media scrutiny of the facility was hampering efforts. Recruitment was not maintaining pace with attrition levels, and this was compounded by high rates of workers’ compensation and daily staff absences. During our inspection of Acacia Prison, the facility was also undertaking recruitment to help address ongoing vacancies.

Some regional facilities, particularly those in the Kimberley and Pilbara, also faced additional difficulties in securing suitable accommodation for staff willing to transfer in. Others, like Eastern Goldfields Regional Prison had trouble attracting and retaining staff.

These shortages have a range of impacts on the operation of custodial facilities. Staff from non-essential areas are regularly re-deployed to ensure there are enough to safely operate core functions. This negatively impacts the delivery of organised recreation, education and programs. Workshops used for training and employment may close and, in some cases, visits may be cancelled, and external appointments may be rescheduled. These impacts cause frustration for both staff and people in custody, which increases the temperature of the facility and affects staff morale.

To help tackle this issue, the Department recently announced a review of staffing across the custodial estate with an intention of modernising employment practices and improving the flexibility and efficiency of the workforce. It was encouraging to see the problem being addressed at a strategic level and we look forward to hearing more about the outcomes of this important piece of work.

Through our work we continue to observe inadequacies across key prisoner support services such as the Aboriginal Visitors Scheme (AVS), Prison Support Officers (PSO) and peer support prisoners. These roles were introduced following the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and serve an important function delivering peer-based support to help identify deterioration in mental health and prevent acts of self-harm and suicide.

Staff shortages continue to impact the effectiveness of these services in many facilities. Under the AVS, local Aboriginal visitors are employed by the Department to provide assistance, support and cultural connections to Aboriginal prisoners. However, in March 2022, over half (15 FTE) of the 27 AVS positions across the custodial estate were vacant. Six facilities – four with a high proportion of Aboriginal prisoners – had no Aboriginal visitors employed (OICS, 2023D).

The level of service between facilities also differs. Between March 2021 and March 2022, the AVS conducted 1,356 visits to Casuarina Prison but only 231 visits to Acacia Prison, despite both facilities having a similar daily average population. And, Boronia Pre-Release Centre, Karnet Prison Farm and Pardelup Prison Farm do not have their own dedicated AVS staff making them reliant on other facilities or leaving prisoners to access the service through telephone contact (OICS, 2023D).

We have highlighted issues and concerns around the delivery of the AVS across multiple reports, including Boronia Pre-Release Centre (OICS, 2022B), Broome Regional Prison (OICS, 2020A), Hakea Prison (OICS, 2022C), Greenough Regional Prison (OICS, 2022D), West Kimberley Regional Prison (OICS, 2021B), Roebourne Regional Prison (OICS, 2022F), and Wooroloo Prison Farm (OICS, 2022A) and in two thematic reviews (OICS, 2022H; OICS, 2023D). The Department has conducted various reviews into the service over the years and is currently working on a revision to the model to improve its functionality. In the meantime, we remain concerned that the purpose and intent of the AVS is not being achieved, which may come at the expense of the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal people in custody.

Similarly, there have been shortages in PSOs across the custodial estate. PSOs help support and coordinate peer support prisoners, who are a valuable resource to other prisoners – particularly outside core business hours. These roles form a key part of the Department’s approach to suicide prevention. In March 2022, there were four PSO positions vacant across the estate and Boronia, Broome and Pardelup had no dedicated position (OICS, 2023D).

At the time of our 2022 Roebourne inspection the PSO had resigned and had not yet been replaced. The PSO had built a strong team of peer support prisoners who worked well with others to provide support and assistance (OICS, 2022F). But without the support of a dedicated PSO, we observed the team becoming less effective and supported in their work. Additionally, the prison had also been without an Aboriginal Visitor since our previous inspection three years prior. The death of a prisoner at Roebourne in 2020 highlights the importance of effective suicide prevention measures. We recommended the Department urgently recruit a PSO and AVS staff to help ensure there is an effective support network in place for prisoners.

Similarly, when we inspected Acacia Prison there were no PSOs on-site (OICS, 2023A). One position had remained vacant for some time and the other was on an extended absence. We were also concerned to see peer support prisoners interviewing at-risk prisoners and providing notes, a role usually reserved for the PSOs, who would then report back to the Prisoner Risk Assessment Group (PRAG). While there are benefits to having a fellow peer check-in with at-risk prisoners, only one peer support prisoner had completed the Gatekeeper Suicide Awareness program and there was limited support and supervision. We recommended Serco review the appropriateness of this arrangement and ensure there were sufficient Prison Support Officers to provide adequate supervision.

In the youth detention space, Aboriginal Youth Support Officers (AYSO) provide a valuable role to young people in custody but historically have also been under-resourced. During our inspection in February 2023, there were only four AYSO positions to cater for youth at both Banksia Hill and Unit 18 at Casuarina Prison (OICS, 2023B). But an additional nine positions had been created in response to our previous inspection and by April 2023 the Department had filled all these roles.

Prevention of self-harm and suicide in custody requires a multi-pronged approach of interventions and supports from custodial staff, non-custodial staff and peer support programs. The absence of an effective peer support mechanism within a custodial facility weakens the Department’s safeguards.

We continue to encourage the Department to take the necessary actions to ensure these important roles are well equipped and resourced to perform their vital work.

As in previous years, we have observed that many people in custody who have mental health concerns, especially those in crisis, have struggled to access adequate care.

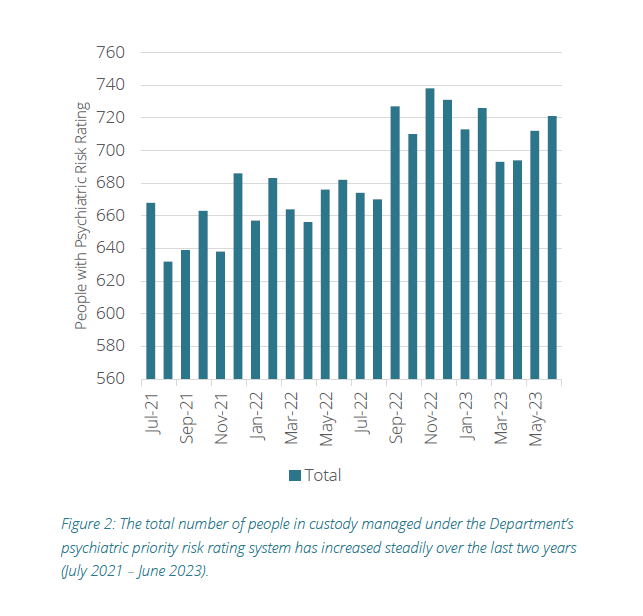

Last financial year we noted a decrease in the number of people in custody being managed under the Department’s psychiatric priority risk rating system (OICS, 2022J). However, this year the number has increased to an average of just over 700 people at any one time. Consequently, this financial year we have made six recommendations seeking assurances that people in custody receive appropriate mental health assessments and support services (OICS, 2023D; OICS, 2023C; OICS, 2022I).

Fortunately, the proposed mental health unit due to be constructed at Casuarina Prison in 2024 is still planned (OICS, 2023C). The 34-bed unit is expected to improve mental health services available for men across the custodial estate, whereas Bindi Bindi, the sub-acute step-up/step down mental health unit at Bandyup Women’s Prison, has shown promise for women in custody. In youth detention, a purpose-built crisis care unit is planned for Banksia Hill Detention Centre. All of these facilities will go some way to improving the mental health support available in prisons and youth detention centres.

We also welcome the State Government’s announcement earlier this year that it is expanding mental health services in the community. New funding in the 2023-24 State budget has been allocated to enable the ‘construction of at least 53 additional forensic mental health beds, of which five are for a children and adolescent unit (Government of Western Australia, 2023).

This is a much-needed investment as we have often reported on the impact that the bed blockages at the Frankland Centre have on the custodial estate (OICS, 2023C; OICS, 2022I; OICS, 2021; OICS, 2018).

By far our biggest concern this year has been Banksia Hill Detention Centre and Unit 18 at Casuarina Prison. Both centres have continued to attract significant public attention and scrutiny. There has been a significant number of critical incidents including serious self-harm and attempted suicides, worrying staff assaults, fires, prolonged roof ascents, and several riots. Adding to this is the significant shortage of custodial staff which has resulted in excessive time in cell for the young people.

Given all of this, our obligation to monitor the treatment and conditions for young people in custody has added significantly to our workload. For example, we conducted 25 liaison visits to Banksia Hill and Unit 18 over the last financial year (out of a total 78 liaison visits for all facilities). This was in addition to our 10-day inspection in February 2023 for which we had to fast track our reporting. Our IVs also visited 11 times compared to six in 2021–2022. All these activities are resource intensive and require a difficult balancing of priorities.

Providing this vital oversight improves transparency, ensures accountability and promotes humanity and decency. But we have not had any additional resources, and consequently, we have been required to risk assess and reprioritise our liaison oversight of other facilities in order to meet this need.

Reporting on the crisis in youth detention has also emphasised a somewhat unusual provision within our Act that delays timely reporting of our inspection and review findings. Section 35 of the Act requires our reports to be laid before both Houses of Parliament for minimum of 30 days before they can be tabled and publicly released.

This timeframe is substantial, and we are not aware of similar reporting arrangements in the statutes of other oversight agencies. As we have seen, much can occur in 30 days, particularly when it relates to youth custody.

For example, our most recent inspection report of Banksia Hill and Unit 18 was laid before both Houses on 8 May 2023, one day prior to the riot on 9–10 May 2023. The report was embargoed until 8 June 2023 and although many of the findings remained relevant, the landscape shifted so significantly during that time, that we believe Section 35 of the Act requires review to ensure the prompt reporting of our statutory responsibilities.

Page last updated: 13 Mar 2024